| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

===Limits of Continuous functions=== | ===Limits of Continuous functions=== | ||

| − | For the majority of limits the limit can just be found by plugging the values into the function. | + | For the majority of limits the limit can just be found by plugging the values into the function. |

For example <math> \lim_{x\to 2}x^2+2x+1=2(2)^2+2(2)+1 </math> | For example <math> \lim_{x\to 2}x^2+2x+1=2(2)^2+2(2)+1 </math> | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

For example. <math> \lim_{x\to 2^{-}}2x+1=5</math>. Notice that just because its <math>2^{-}</math> DOES NOT make it the same as <math>-2</math>. This means we take the limit as we approach the point 2 from numbers slightly less than 2. The same is true in reverse for <math>2^{+}</math> | For example. <math> \lim_{x\to 2^{-}}2x+1=5</math>. Notice that just because its <math>2^{-}</math> DOES NOT make it the same as <math>-2</math>. This means we take the limit as we approach the point 2 from numbers slightly less than 2. The same is true in reverse for <math>2^{+}</math> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Dividing by Zero and Infinity??=== |

| − | To set the record straight before we begin, infinity does not work like any other run of the mill number. It is, specifically by definition, not a number. A quick example of why not would be | + | To set the record straight before we begin, infinity does not work like any other run of the mill number. It is, specifically by definition, not a number. A quick example of why not would be |

| − | + | ||

| + | <math>\infty + 3=\infty\\ | ||

\infty - \infty + 3 =\infty - \infty\\ | \infty - \infty + 3 =\infty - \infty\\ | ||

| − | |||

3=0</math> | 3=0</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | As I'm sure you all have experienced, divide by zero errors are the bane of any mathematician. Lets try to find if there is a way to get close but not quite zero and see what that is. What better way to do this than with our new found tool. The limit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lets see what happens if we do <math>\lim_{x\to 0}\frac{1}{x}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can't just plug it in like before and there's nothing we can cancel it out with, so lets just get closer and closer by hand. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we set <math>x=.1, \frac{1}{x}=10</math>, getting closer <math>x=.001, \frac{1}{x}=1000</math>, even closer, <math>x=.000001, \frac{1}{x}=1000000</math>. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This seems pretty pointless, the smaller the number we put in the bigger the number we get out seemingly without end. Let's just make a name for this concept of a value without an highest bound and call it fibigy or better yet infinity. <font size=1>(Note that we are not saying that infinity is this number but rather a concept for a value without anything higher than it)</font size> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now that we've made this "new" term, <math>\infty</math>, we can say that <math>\lim_{x\to 0}\frac{1}{x}=\infty</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We can try a similar process in reverse with this new found term infinity | ||

| + | |||

| + | I wonder what <math>\lim{x\to\infty}\frac{1/x}</math> is? | ||

| + | |||

| + | If we try the same method we tried with 0 we keep getting smaller and smaller numbers as we use higher and higher values of x | ||

| + | |||

| + | We know for sure that this value can never be negative since the numbers only get larger positive, and we know that the numbers will never stop getting lower. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Combined we can pick the smallest not negative number we can find, 0. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This makes sense <math>\lim{x\to\infty}\frac{1/x}=0</math> and <math>\lim{x\to 0}\frac{1/x}=\infty</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now we can apply these two limits to problems that look much more difficult than they are. | ||

| + | |||

| + | CAUTION | ||

| + | |||

| + | :We cannot say that <math>\frac{1}{0}=\infty</math> for similar reasons to why we cannot use infinity as a number | ||

| + | |||

| + | :For example <math>1*\frac{1}{0}=\infty=\frac{2}{0}=2*\frac{1}{0}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :<math>1=2</math> | ||

Revision as of 01:03, 1 November 2017

Work in Progress

Limits Approaching Infinity Intuitively

by Kevin LaMaster, proud Member of the Math Squad.

Contents

Introduction

I've noticed that many calculus one students loathe taking limits specifically as they approach infinity. This series should not be an introduction to limits nor should it replace a strict definition for a limit. Both of those can be found better at this tutorial. This only serves for a crash course tutor replacement for Calculus 1 students struggling with some difficult homework.

Basic Limits

Just as a recap over basic limits not into infinity.

Limits of Continuous functions

For the majority of limits the limit can just be found by plugging the values into the function.

For example $ \lim_{x\to 2}x^2+2x+1=2(2)^2+2(2)+1 $

The definition of a continuous function is that the limit at any point is equal to the value at that point.

The complicated math way to say this is $ \lim{x\to x_0}f(x)=f(x_0) $

This makes sense. If a function is continuous then every point is exactly where we would "expect it to be".

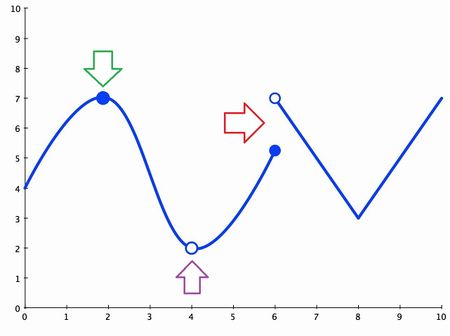

As you can see by the graph, the green arrow shows a point on the graph that is exactly where we would expect it to be. The graph is continuous at this point.

The purple arrow shows a place where we would expect a point, but there isn't one there. The graph isn't continuous at that point.

The red arrow shows a point where we don't know what to expect. Coming from the left it looks like the graph should be the lower point. But coming from the right we would expect it to be the higher point. Since the function can't do both it isn't continuous at this point. This topic of approaching a limit from one direction or another brings us to our next topic.

Directional Limits

In the case of the graph above we may want to know the limit as we approach a point strictly from the left or from the right. We show this in our limit with a small plus or minus sign floating above the value.

For example. $ \lim_{x\to 2^{-}}2x+1=5 $. Notice that just because its $ 2^{-} $ DOES NOT make it the same as $ -2 $. This means we take the limit as we approach the point 2 from numbers slightly less than 2. The same is true in reverse for $ 2^{+} $

Dividing by Zero and Infinity??

To set the record straight before we begin, infinity does not work like any other run of the mill number. It is, specifically by definition, not a number. A quick example of why not would be

$ \infty + 3=\infty\\ \infty - \infty + 3 =\infty - \infty\\ 3=0 $

As I'm sure you all have experienced, divide by zero errors are the bane of any mathematician. Lets try to find if there is a way to get close but not quite zero and see what that is. What better way to do this than with our new found tool. The limit.

Lets see what happens if we do $ \lim_{x\to 0}\frac{1}{x} $

We can't just plug it in like before and there's nothing we can cancel it out with, so lets just get closer and closer by hand.

If we set $ x=.1, \frac{1}{x}=10 $, getting closer $ x=.001, \frac{1}{x}=1000 $, even closer, $ x=.000001, \frac{1}{x}=1000000 $.

This seems pretty pointless, the smaller the number we put in the bigger the number we get out seemingly without end. Let's just make a name for this concept of a value without an highest bound and call it fibigy or better yet infinity. (Note that we are not saying that infinity is this number but rather a concept for a value without anything higher than it)

Now that we've made this "new" term, $ \infty $, we can say that $ \lim_{x\to 0}\frac{1}{x}=\infty $

We can try a similar process in reverse with this new found term infinity

I wonder what $ \lim{x\to\infty}\frac{1/x} $ is?

If we try the same method we tried with 0 we keep getting smaller and smaller numbers as we use higher and higher values of x

We know for sure that this value can never be negative since the numbers only get larger positive, and we know that the numbers will never stop getting lower.

Combined we can pick the smallest not negative number we can find, 0.

This makes sense $ \lim{x\to\infty}\frac{1/x}=0 $ and $ \lim{x\to 0}\frac{1/x}=\infty $

Now we can apply these two limits to problems that look much more difficult than they are.

CAUTION

- We cannot say that $ \frac{1}{0}=\infty $ for similar reasons to why we cannot use infinity as a number

- For example $ 1*\frac{1}{0}=\infty=\frac{2}{0}=2*\frac{1}{0} $

- $ 1=2 $